Sugar in ice cream

If you find the content on this blog useful and would like to see more of it, please consider supporting my work on Patreon.

Ice cream generally contains seven categories of ingredients: fat (dairy or nondairy), milk solids-not-fat (MSNF) (the lactose, proteins, minerals, water-soluble vitamins, enzymes, and some minor constituents), sweeteners, stabilisers, emulsifiers, water, and flavours (Goff & Hartel, 2013). In this post, we’ll be looking at the role of sweeteners in ice cream.

You might also like to read:

The best ice cream maker 2020 - A comprehensive guideLello 4080 Musso Lussino Ice Cream Maker - A Comprehensive ReviewCuisinart ICE-100 Ice Cream Maker - A Comprehensive ReviewHow To Calculate An Ice Cream MixLocust Bean Gum in Ice CreamVanilla Ice Cream - Recipe[toc]

1. Which sweeteners are used in ice cream?

Sweeteners used in ice cream include cane and beet sucrose (‘sugar’), invert sugar, Corn Starch Hydrolysate Syrup (CSS), high maltose syrup, fructose or high fructose syrup, maltodextrin, dextrose, maple syrup or maple sugar, honey, brown sugar, and lactose. Because these sweeteners contribute metabolisable energy to the diet, they are called 'nutritive' or 'caloric' sweeteners. The most common choice of nutritive sweetener is a combination of sucrose (10-12%) and CSS (3-5%) (Goff & Hartel, 2013).

Below is a table showing suggested mix compositions for ice cream, from Goff & Hartel (2013).

2. Why are sweeteners used in ice cream?

The primary purposes for using sweeteners in ice cream are: to provide sweetness and enhance flavour; to develop smooth and creamy texture; to make ice cream softer and easier to scoop; and to contribute total solids.

2.1. Sweetness and flavour enhancement

The main function of sweeteners is to increase the acceptance of ice cream by making it sweet and by enhancing the pleasing creamy flavour. Lack of sweetness produces a flat taste; too much tends to mask desirable flavours (Goff & Hartel, 2013).

2.1.1. Relative Sweetness

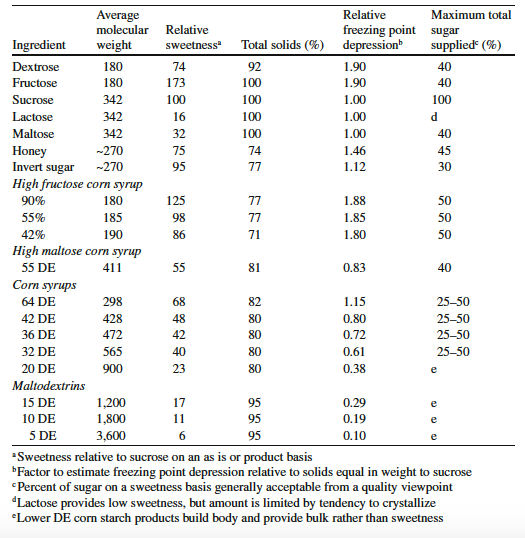

Sweeteners differ in their relative sweetness. Relative sweetness is a means of ranking sweeteners in comparison to one another. Sucrose is used as the standard and has a relative sweetness value of 100. Fructose, which has a relative sweetness value of 173, is the sweetest nutritive sweetener, whilst maltodextrins, having a relative sweetness value of between 6 and 17, have a bland taste with very little sweetness.

Below is a table showing the characteristics of sweeteners in ice cream, from Goff & Hartel (2013).

2.1.2. Sweetness Perception

As well as having different sweetness values, sweeteners also differ in the way that their sweetness is perceived. Sucrose imparts a sweetness that is slow to develop and slow to decay. If used in excess, its broad sweetness profile can mask flavours that are perceived at the same time. The sweetness perception profile of High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) is the sum of those of its constituent sugars, fructose and glucose (dextrose). Fructose has a very intense sweetness that only lasts for a short period of time. Dextrose is less sweet than either fructose or sucrose. Its perceived sweetness lasts for longer than that of fructose, but less than that of sucrose (Hull, 2010). Because perception of the sugars in fructose-only or HFCS-sweetened ice cream decays faster than sucrose, these sweeteners are said to enhance the flavours of fruits and spices that are masked to a degree by sucrose (White, 2014).

Below is a profile of sweetness response, from Hull (2010).

2.2. Develop smooth and creamy texture

Besides enhancing sweetness and flavour, nutritive sweeteners also determine textural creaminess and mouthfeel (Stampanoni, 1993; Guinard et al., 1997). In general, increasing the sweetener level increases creaminess as a result of the reduction in the size of ice crystals. Smooth and creamy ice cream requires the majority of ice crystals to be small. If many crystals are large, the ice cream will be perceived as being coarse or icy.

Sweeteners influence ice crystal size by two main mechanisms: 1. specific effects on ice crystallisation, and 2. effect on freezing point depression.

2.2.1. Ice Crystallisation

To control ice crystal size, it is important to develop an understanding of ice formation (known as crystallisation) during the freezing of ice cream. Ice cream is frozen in two stages, the first being a dynamic process where the mix is frozen in a scraped-surface freezer (SSF) (an ice cream machine) whilst being agitated by the rotating dasher, a mixing device with sharp scraper blades attached, to incorporate air, destabilise the fat, and form ice crystals. Upon exiting the SSF, the ice cream, at about -5°C to -6°C (23°F to 21.2°F) and with a consistency similar to soft-serve ice cream, undergoes static freezing where it is hardened in a freezer without agitation until the core reaches a specified temperature, usually -18°C (-0.4°F).

During dynamic freezing, the ice cream mix is added to the SSF at between 0°C and 4°C (32°F and 39.2°F). As the refrigerant absorbs the heat in the mix, a layer of water freezes to the cold barrel wall causing rapid nucleation (the birth of small ice crystals) (Hartel, 2001). The crystals that form at the cold barrel wall are then scraped off by the rotating scraper blades and dispersed into the centre of the barrel where warmer mix temperatures cause some crystals to melt and others to grow and undergo recrystallisation.

Recrystallisation is defined as “any change in number, size, shape… of crystals” (Fennema, 1973) and basically involves small crystals disappearing, large crystals growing, and crystals fusing together, all of which result in an overall increase in ice crystal size. Russell et al. (1999) found that crystallisation during the freezing of ice cream is dominated by recrystallisation and growth and that these mechanisms appear to be more important than nucleation in determining the final crystal population.

In general, as the concentration of a sweetener is increased, ice crystals become smaller owing to a reduction in ice crystal growth rate and delayed nucleation during dynamic freezing (Omran & Kind, 1974; Hartel, 1996; Haddad Amamou et al., 2010). This effect can be explained by two facts. First, the higher viscosity (thicker mix) promotes crystal melting and attrition. Second, the solution has a higher resistance to water diffusion (movement of melted liquid from smaller ice crystals to the surface of larger ice crystals) at higher concentrations of sweetener (Haddad Amamou et al., 2010).

2.2.2. Freezing Point Depression

The freezing point of pure water is 0°C (32°F). When a substance is dissolved in water, however, the temperature at which the water freezes is lowered. This lowering of the freezing point is referred to as the ‘Freezing Point Depression’ and is defined as the difference between 0°C (32°F) and the temperature at which water in an ice cream mix first begins to freeze (Goff & Hartel, 2013). Freezing point depression is influenced primarily by sweeteners (including the lactose in milk) and milk salts. Increasing the amount of these solutes will lower the freezing point of an ice cream mix, resulting in less ice being formed at a given temperature.

Freezing point depression affects the rate of recrystallisation during static freezing, the softness and scoopability of ice cream, and the rate at which ice cream melts during consumption.

2.2.2.1. Recrystallisation during storage

As ice cream sits in storage, the ice crystals continually grow by recrystallisation (Donhowe & Hartel, 1996; Hartel, 1998). This increase in crystal size eventually reaches a point where the ice cream develops coarse texture, at which point it has surpassed its shelf life. Several studies have found a direct relationship between recrystallisation rate and freezing point; that is, the lower the freezing point, the higher the recrystallisation rate during storage (Hagiwara & Hartel, 1996; Harper & Shoemaker, 1983; Miller-Liveney & Hartel, 1997). This is because as the freezing point is depressed, the amount of unfrozen water increases, and this unfrozen water will participate readily in recrystallisation during storage.

Different sweeteners depress the freezing point of water to different extents, depending on the number of small molecules in the mix. The lower the molecular weight of a sweetener, the greater the effect it will have on lowering the freezing point. Dextrose and fructose, having nearly half the molecular weight of sucrose, will be twice as effective at lowering the freezing point than an equivalent weight of sucrose. 20 DE CSS will actually cause an increase in the freezing point compared with that for sucrose.Investigating the effects of various sweeteners (sucrose, 20 DE CSS, 42 DE CSS, and 42% HFCS) and stabilisers on ice recrystallisation during storage, Hagiwara & Hartel (1996) found that ice creams containing HFCS exhibited the highest recrystallisation rates, whereas ice creams made with 20 DE or 42 DE CSS had the lowest recrystallisation rates. These findings were attributed to the greater freezing point depression caused by HFCS (-4.4°C (24°F)) compared to 20 DE CSS (-1.7°C (28.9°F)).

2.2.2.2. Softness and scoopability

Sweeteners are also responsible for the softness and scoopability of ice cream through their effect on freezing point depression. A high sweetener content will generally produce soft ice cream owing to a low freezing point and the subsequent reduction in the ice phase volume (the amount of frozen water). If the sweetener used is sucrose, the freezing point is likely to be high and the ice cream hard. Similarly, ice cream made with 20 DE CSS will likely have a high freezing point and hard texture. If sucrose is replaced with either dextrose or fructose, the freezing point is likely to be low, resulting in less frozen water and softer ice cream.

2.2.2.3. Melting rate

The type and amount of sweetener also affects the melting rate of ice cream during consumption, with a lower freezing point leading to an increased rate of melting (Muse & Hartel, 2004; Junior & Lannes, 2011; Goff & Hartel, 2013). Ice cream made with either dextrose or fructose will have a higher melting rate because of a lower freezing point, whereas ice cream made with 20 DE CSS will have a slower melting rate because of a higher freezing point.

2.3. Contribute Total Solids

Ice crystal size is related inversely to the total solids (the fat, MSNF, sweetener, egg yolk solids, and stabiliser and emulsifier) of an ice cream mix; that is, ice cream made from a mix with a higher total solids content generally contains smaller ice crystals (Donhowe et al., 1991; Guinard et al., 1997). The theory behind this is that an increase in the level of total solids in the mix will lower the amount of water and thereby reduce the total amount of ice formed. Because of their low sweetness value, CSS (20 to 64 DE), lactose, and maltose, are a convenient and cost-effective way of increasing total solids without introducing excessive sweetness.

3. Summary

Nutritive sweeteners are used in ice cream primarily to provide sweetness, promote smooth and creamy texture by reducing ice crystal growth during dynamic freezing, produce softer ice cream that is easier to scoop, and to contribute to the total solids content of a mix, thereby reducing the size of the ice crystals. Excessive sweetener use, however, will likely mask flavours, increase recrystallisation rates during storage, thereby limiting shelf life, and produce ice cream that melts quickly during consumption.

4. References

Donhowe, D. P., Hartel R. W., and Bradley R.L., 1991. Determination of ice crystal size distributions in frozen desserts. J. Dairy Sci. 74.

Donhowe, D. P., and Hartel, R. W., 1996. Recrystallization of ice in ice cream during controlled accelerated storage. Int Dairy J, 6 (11–12):1191–208.

Fennema, O. R., Powrie, W. D., Marth, E. H., 1973. Low Temperature Preservation of Foods and living Matter. USA: Marcel Dekker, Inc.

Goff, H. D., and Hartel R. W., 2013. Ice Cream. Seventh Edition. New York: Springer.

Guinard, J. X., Zoumas Morse, C., Mori, L., Uatoni, B., Panyam, D., and Kilara, A., 1997. Sugar and Fat Effects on Sensory Properties of Ice Cream. Journal of Food Science. 62.5.

Haddad Amamou, A., Benkhelifa, H., Alvarez, G., and Flick, D., 2010. Study of crystal size evolution by focused-bean reflectance measurement during the freezing of sucrose/water solutions in a scraped-surface heat exchanger. Process Biochemistry. 45. 1821-1825.

Hagiwara, T., and Hartel, R. W. 1996. Effect of sweetener, stabilizer, and storage temperature on ice recrystallization in ice cream. J Dairy Sci. 79(5):735–44.

Harper, E. K., and Shoemaker, C. F., 1983. Effect of locust bean gum and selected sweetening agents on ice recrystallization rates. J. Food Sci. 48:1801.

Hartel, R. W., 1996. Ice crystallisation during the manufacture of ice cream. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 7(10).

Hartel, R. W., 1998. Phase transitions in ice cream. In: RaoMA, Hartel RW, editors. Phase/state transitions in foods: chemical, structural, and rheological changes. IFT basic symposium series. New York: Marcel Dekker. p 327–68.

Hull, P., 2010. Glucose Syrups, Technology and Applications. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell.

Junior, E. D. S., and Lannes, S. C. D. S., 2011. Effect of different sweetener blends and fat types on ice cream properties. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment., Campinas. 31(1), 217-220.

Miller-Livney T., and Hartel, R. W., 1997. Ice recrystallization in ice cream: interactions between sweeteners and stabilizers. Journal of Dairy Science. 80:447–56.

Muse, M. R., and Hartel, R. W., 2004. Ice Cream Structural Elements that Affect Melting Rate and Hardness. Journal of Dairy Science. 87, 1-10.

Omran, A. M., and King, C. J., 1974. Kinetics of ice crystallization in sugar solutions and fruit juices. AIChE Journal. 20(4). 795–803.

Russell, A. B., Cheney, P. E., and Wantling, S. D., 1999. Influence of freezing conditions on ice crystallisation in ice cream. Journal of Food Engineering. 29.

Stampanoni, C. R., 1993. Influence of acid and sugar content on sweetness, sourness and the flavor profile of beverages and sherbets. Food Qual. Pref., 4. 169–176.

Sutton, R., and Bracey, J., 1996. The blast factor. Dairy Industries International, 61(2). 31-33.

White, J. S., 2014. Sucrose, HFCS, and Fructose: History, Manufacture, Composition, Apllications, and Production. In J. M. Rippe (ed), Fructose, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Sucrose and Health, Nutrition and Health. New York: Springer.