How to make vanilla extract

12 MINUTE READIn this post, I will put forward an optimised method for the production of homemade vanilla extract and will discuss the factors that influence its quality. These include the bean quality, bean particle size, ethanol concentration, and ageing of the extract.[toc]

1. The Vanilla Plant

Vanilla is a tropical epiphytic orchid of the family Orchidaceae (Childers et al., 1959). About 110 vanilla species have been identified, but only two are of commercial importance today: Vanilla planifolia Andrews, also known as Vanilla fragrans (Salisbury), and Vanilla tahitensis JW Moore (Purseglove et al., 1981). In the United States, these are the only species permitted to be used in food products. The main growing areas of Vanilla planifolia include the 'Bourbon' Islands (the term used collectively for beans from Madagascar, Reunion, Comoro Islands, and the Seychelles), Indonesia, Mexico, Tonga, and India, while Tahiti, Papua New Guinea, and limited parts of Indonesia produce mainly Vanilla tahitensis.

The fruit of a fully mature vanilla orchid is called a vanilla ‘pod’ or ‘bean’. These beans are green, long, smooth, and slender (somewhat resembling a large green bean), possess no flavour, and are almost odourless. To develop the characteristic vanilla flavour and aroma, green beans are subjected to a curing process commonly lasting three to six months. When properly cured, vanilla beans should resemble long, very thin cigarillos; supple, very dark brown, a raisin-like texture and somewhat oily sheen. High-quality beans may have white crystals of vanillin clinging to the outside, but this is rarely seen today (Gillette & Hoffman, 2000).Cured vanilla beans can be used as they are, but the vast majority are used for the extraction and the preparation of vanilla products, of which there are four basic types: vanilla extract, by far the most used vanilla product, vanilla oleoresin, vanilla absolute, and vanilla powder/sugar.

2. Vanilla Extract

2.1 Definition

In the U.S Code of Federal Regulations for Vanilla, 21CFR169.175 169.182, vanilla extract is defined as the solution in aqueous ethyl alcohol of the sapid and odorous principles extractible from vanilla beans. In vanilla extract, the content of ethyl alcohol is not less than 35 percent by volume and the content of vanilla constituent is not less than one unit per gallon.

The term ‘unit’ means, in the case of vanilla beans containing not more than 25 percent moisture, 13.35 ounces of such beans, and, in the case of vanilla beans containing more than 25 percent moisture, it means the weight of such beans equivalent in content of moisture-free vanilla bean solids to 13.35 ounces of vanilla beans containing 25 percent moisture. This amounts to not less than 10.0125 oz (FDA standard) of dry weight solids.

Vanilla extract may contain one or more of the following ingredients:

- Glycerin

- Propylene glycol (usually no more than 2%)

- Sugar (including invert sugar)

- Dextrose

- Corn Syrup (or corn syrup solids)

2.2 What is vanilla 'fold'?

The concentration of an extract is noted by its ‘fold’, with vanilla extracts available in 1 to 10 fold strength. A single fold of vanilla extract contains the extractable material from 13.35 oz of vanilla beans per gallon of solvent, or 100g of extractable material per litre, whereas a ten-fold product contains the extractable material from 1kg of beans per 1 litre of solvent. Almost all household extracts are single-fold strength, with two-fold and higher strength extracts being preferred by industrial food manufacturers.

2.3 What influences the quality of vanilla extract?

Several factors influence the quality of vanilla extract. These include 1. the quality of the beans, 2. bean particle size, 3. ethanol concentration, and 4. appropriate period of ageing (Broderick, 1955; Merory, 1969; Heath and Reineccius, 1986).

2.3.1 Bean quality

Most experts generally consider the flavour of a high vanillin (>0.20%), high moisture (>20%) Bourbon bean to deliver the best quality extract.

2.3.1.1 A high vanillin content

Although vanilla extract contains more than 300 compounds (Toth et al., 2011), the most commonly associated with vanilla extract quality are 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (vanillin), vanillic acid, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (Havkin-Frenkel et al., 2011). Of these, vanillin is the most abundant and generally used as the prime indicator of flavour quality of extracts: the lower the vanillin content, the lower the flavour quality of the bean will be, not just because of the vanillin itself, but also due to the other flavour notes which develop along with vanillin during curing.

Vanillin is present in single-fold extracts at levels ranging from 0.2 per 100 ml (0.2%) for a good quality extract to less than 0.02 per 100 mL (0.02%) for inferior quality product (Ranadive, 2011). Vanilla extracts made from Indian vanilla beans tend to yield vanillin content in the range of 0.2 to 0.25% per fold, whereas beans from Madagascar are averaging less than 0.18% vanillin content per fold (Ranadive, 2011).

The vanillin content alone does not, however, constitute vanilla flavour; vanillin alone is probably responsible for no more than 25% of the character of quality vanilla extract. Gillette & Hoffman (2000) note that flavour notes such as pruney, woody, floral, fruity, and rummy, which develop along with vanillin during curing, are even more important than vanillin character alone. In some cases, extracts with high amounts of vanillin will not taste as good as other extracts with lower vanillin content but containing the other flavour components

2.3.1.2 Moisture Content

The moisture content of commercial vanilla beans varies from 10% for poor quality lower grade beans to 35% for gourmet beans (Ranadive, 2011). 'Extraction' grade beans contain from 20 to 25% moisture, the maximum limit set by the US standard of identity. Drier beans are less aromatic than high moisture beans and flavour notes, such as pruney, woody, floral, fruity, and rummy, which develop along with vanillin during curing, do not develop and/or are lost, in over-dried (low moisture) beans (Gillette & Hoffman, 2000).

2.3.2 Bean particles size

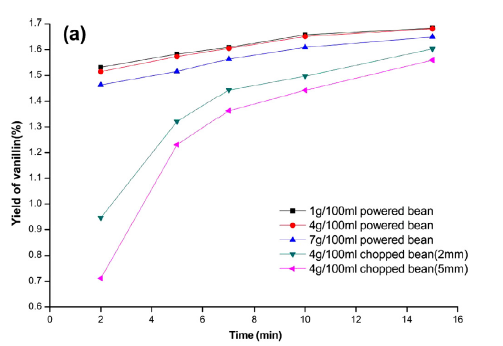

Dong et al. (2013) compared three different bean particle sizes (2mm and 5mm chopped beans, and powdered beans) in the production of vanilla extract using Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE). Their results showed that vanillin yield increased with decreasing particle sizes: powdered beans had higher yield than that of chopped vanilla beans. The researchers also found that sloshing around the container of the powdered vanilla beans improved the extraction efficiency of the beans.

2.3.3 Ethanol Concentration

The extraction of vanillin from cured vanilla beans is greatly influenced by the ethanol percentage in the solvent. Changes in ethanol concentration mainly affect the polarity (whether a liquid will mix with another liquid) of the solvent. Dong et al. (2013) found that a 70% ethanol concentration may possess similar polarity to vanillin and give a higher yield than 40% and 100% ethanol concentrations. Jadhav et al. (2009) found that when the ethanol volume percentage in the solvent was lower than 50% (v/v) during conventional extraction, the extraction increased with the increase of ethanol concentration (from about 85 ppm at 30% ethanol to about 120 ppm of vanillin extraction at 50% ethanol). However, beyond this concentration, any further increase was found to be detrimental for the extraction process (the extent of vanillin extraction decreased gradually to about 105 ppm for 100% ethanol). Thus, a 1:1 v/v ethanol/water solution resulted in maximum extraction of vanillin from cured vanilla beans during conventional extraction.

2.3.4 Ageing

Freshly made vanilla extract has a slightly harsh alcohol bite, unless tempered with the addition of sugar syrup or glycerin. Like a fine wine, the flavour of vanilla extract mellows and improves as it ages. A minimum of 60 days ageing of a finished extract is advisable to develop the resinous, Bourbon character fully (Gillette & Hoffman, 2000). Stored under proper conditions (60-65°F) and away from light, vanilla develops pleasant, sweet, somewhat complex and mellow notes (Ranadive, 2011). Vanilla extract continuous to improve over a several year period until it more resembles a delightful liquor than vanilla extract. Storage in oak barrels (new or previously used for whiskey) is a traditional method for vanilla.

2.4 How to make a single-fold vanilla extract

This process yields about 500ml of vanilla extract. Weigh 50g of grade A beans. In a spice, or coffee, grinder, finely grind the beans and add to a 500ml glass jar. Add 250ml of 50% vodka and close the jar. Leave to steep at room temperature for at least 12 hours, sloshing the ground beans around the jar once every hour. Decant the extract into a separate 500ml glass jar using a fine sieve to remove the ground beans. Close the jar and store at room temperature and away from light. Place the sieved ground beans back into the first jar and add 250ml of fresh 50% vodka. Close the jar and leave to infuse at room temperature for at least 12 hours, sloshing the ground beans around the jar once every hour. At the end of this period, decant the extract into the jar containing the first extract using a fine sieve to remove the ground beans, which can now be discarded. The combined solutions produce a complete and full-bodied extract. Bring the volume of the combined extract to 500ml with the addition of 50% vodka, if required. Shake well. Age the extract for a minimum of 60 days at 60°F to 65°F (16°C to 18°C) and away from light.

3. References

3. References

Broderick, J. J., 1955. Vanilla extract manufacture. A guide to choice of method. Food Manuf., 30(1): 65–8.

Childers, N. F., Cibes, H. R., and Hernande-Medina, E., Vanilla – the orchid of commerce. In: Wither, C. L. ed. 1959. The Orchids, a Scientific Survey. New York: Ronald Press. Pp 477-508.

Dong, Z., Gu, F., Xu, F., and Wang, Q., 2014. Comparison of four kinds of extraction techniques and kinetics of microwave-assisted extraction of vanillin from Vanilla planifolia Andrews. Food Chemistry. 149. 54-61.

Gillette, M., and Hoffman, P., 2000. Vanilla extract. In: Francis, F.J. ed. 2000. Encyclopedia of Food Science and Technology. 2nd Edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 2383–2399.

Havkin-Frenkel, D., Belanger, F. C., Booth, D. Y. J., Galasso, K. E., Tangel, F. P., and Gayosso, C. J. H. A Comprehensive Study of Composition and Evaluation of Vanilla Extract in US Retail Stores. In: Havkin-Frenkel, D., and Belanger, F. C., ed. 2011. Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Heath, H. B., and Reineccius, G., 1986. Flavor Chemistry and Technology. AVI, CT. Westport.

Jadhav, D., Rekha, B. N., Gogate, P. R., Rathod, V. K., 2009. Extraction of vanillin from vanilla pods: A comparison study of conventional soxhlet and ultrasound assisted extraction. Journal of Food Engineering. 93. 421-426.

Merory, J., 1960. Food Flavorings: Composition, Manufacture and Use. AVI, Westport, CT.

Purseglove, J. W., Brown, E. G., Green, C. L., and Robbins, S. R. J., 1981. Spices, Vol 2, New York, Longman, Inc.

Ranadive, A. S. Quality Control of Vanilla Beans and Extracts. In: Havkin-Frenkel, D., and Belanger, F. C. ed. 2011. Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Rao, S. R., and Ravishankar, G. A., 2000. Review Vanilla flavour: production by conventional and biotechnological routes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 80:289-304

Toth, S., Joong Lee, K., Havkin-Frenkel, D., Belanger, F. C., and Hartman, T., G. Volatile Compounds in Vanilla. In: Havkin-Frenkel, D., and Belanger, F. C. ed. 2011. Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.